National Water-Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Project

Back to "Parking-Lot Sealcoat: A Major Source of PAHs in Urban and Suburban Environments"

What are PAHs, coal tar, and sealcoat? (top of page)

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (or PAHs) are a group of organic contaminants that form from the incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons, such as coal. Coal tar is a byproduct of the coking of coal, and can contain 50 percent or more PAHs by weight.

Sealcoat is a black liquid that is sprayed or painted on asphalt pavement in an effort to protect and beautify the asphalt. Most sealcoat products are coal-tar or asphalt based. Many coal-tar sealcoat products contain as much as 30 percent coal tar by weight.

Where is sealcoat used? (top of page)

Sealcoat is used commercially and by homeowners across the Nation. It commonly is applied to parking lots associated with commercial businesses (including strip malls and shopping centers); apartment and condominium complexes; churches, schools, and business parks; and on residential driveways. The City of Austin, Texas, estimates that about 600,000 gallons of sealcoat are applied every year in the city.

Two kinds of sealcoat products are widely used: coal-tar-emulsion based products and asphalt-emulsion based products. National use numbers are not available; however, it has been suggested that asphalt-based sealcoat is more commonly used on the West Coast and coal-tar based sealcoat is more commonly used in the Midwest, the South, and on the East Coast.

How does sealcoat get from parking lots into the environment? (top of page)

Vehicle tires abrade parking-lot sealcoat into small pieces. These small particles are washed off parking lots by rain into storm sewers and streams. Sealcoat “wear and tear” is visible in high traffic areas within a few months after application, and sealcoat manufacturers recommend reapplication every 2 to 3 years.

How did the USGS study parking-lot runoff? (top of page)

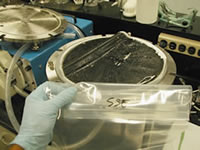

USGS researchers sampled runoff at 13 parking lots representing a range of different sealant types in Austin. They also took scrapings of different parking lot surface types to compare the source material with wash-off particulates. Both the source material and wash-off particulates were analyzed for a suite of PAHs, major elements, and trace elements. The USGS researchers sprayed water on four different types of parking-lot surfaces in Austin, Texas: lots sealed with coal-tar based sealcoat (photo on left), lots sealed with asphalt-based sealcoat, unsealed asphalt lots, and unsealed concrete lots. The runoff was collected behind spill berms, pumped into containers (middle photo) and filtered through Teflon filters to collect the particulates for analysis (photo on right). The particulates, the filtered water, and samples of sealcoat scraped from the parking-lot surfaces were analyzed for PAHs at the USGS National Water Quality Laboratory. Concentrations and yields (the amount of PAHs coming off each lot) were used to determine levels of contamination in runoff from each type of lot and the importance of sealed lots as a source of PAHs to urban streams.

|

|

|

What concentrations of PAHs wash off sealed and unsealed parking lots? (top of page)

The NAWQA study found that concentrations of PAHs were much higher in runoff from parking lots sealed with coal-tar based sealcoat than from all other types of parking-lot surfaces. The average concentration in runoff from coal-tar sealed lots was 3,500 mg/kg, about 65 times higher than the average concentration in particles washed off parking lots that had not been sealcoated (54 mg/kg). The average concentration in particles washed off parking lots sealed with asphalt-based sealcoat was 620 mg/kg, about 6 times less than coal-tar based sealcoat, but still 10 times higher than the concentration from unsealed parking lots (Mahler and others, 2005, Parking Lot Sealcoat: An Unrecognized Source of Urban Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Environmental Science & Technology, v. 39, p. 5560-5566)

Runoff from all parking lots is contaminated with PAHs from leaking motor oil, tire particles, vehicle exhaust, and atmospheric deposition, and therefore, it is not surprising that the concentrations of PAHs in particles washed off each of the different surface types exceeded a widely used consensus-based sediment-quality guideline of 22.8 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg). This sediment-quality guideline, known as the Probable Effect Concentration (PEC) represents the concentration of a contaminant in bed sediment expected to adversely affect benthic, or bottom-dwelling, biota. However, the large differences between concentrations for the sealed and unsealed parking lots indicate that abraded sealcoat is a potentially important (and previously unrecognized) contributor to PAH contamination in urban and suburban water bodies.

How do PAHs from sealcoat impact streams? (top of page)

The USGS assessed connections between PAHs in particles washed from sealed parking lots and PAHs in suspended sediment in four streams in Austin and Fort Worth, Texas. Findings showed that PAHs in suspended sediments in the streams were chemically similar to those in runoff from parking lots sealed with coal-tar based sealcoat. Analysis of the total mass of PAHs expected to wash off sealed parking lots and the total mass of PAHs measured in suspended sediments in the streams after rainstorms indicated that runoff from sealed parking lots could account for the majority of PAH loads to the streams.

Both unsealed and sealed parking lots receive PAHs from the same urban sources—tire particles, leaking motor oil, vehicle exhaust, and atmospheric deposition—yet the average yield of PAHs from sealed parking lots is 50 times greater than that from unsealed lots. What would be the effect on PAH loading to the streams if parking lots were not sealed? Estimates from the USGS study indicate that total loads of PAHs coming from parking lots in the studied watersheds would be reduced to about one-tenth of their current loads if all of the parking lots were unsealed.

City of Austin biologists are conducting studies to evaluate the effects of sealcoated parking lots on aquatic communities in area streams. These studies include toxicity testing (exposing single test organisms to sediments spiked with coal-tar and asphalt-based sealcoat) and evaluations of aquatic communities in streams upstream and downstream from inflows of runoff from sealed parking lots.

What are the environmental and human-health concerns? (top of page)

PAHs found in sealcoat and other combustion-based materials are toxic to mammals (including humans), birds, fish, amphibians, invertebrates, and plants. PAHs tend to attach to sediments; possible effects of PAHs on aquatic invertebrates include inhibited reproduction, delayed emergence, sediment avoidance, and mortality. The Probable Effect Concentration (PEC) for total PAH, a widely used sediment-quality guideline for the concentration of a contaminant in bed sediment expected to adversely affect benthic (or bottom-dwelling) biota, is 22.8 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg). Possible adverse effects on fish include fin erosion, liver abnormalities, cataracts, and immune system impairments.

The USGS study did not evaluate human-health risk from exposure to sealcoat. Human-health risk from environmental contaminants is often evaluated in terms of exposure pathways. For example, people could potentially be exposed to PAHs in sealcoat through skin contact with abraded particles from parking lots, inhalation of wind-blown particles, and inhalation of fumes that volatilize from sealed parking lots. PAHs in streams and lakes rarely pose a human-health risk via drinking water because of their tendency to attach to sediment rather than dissolve in water. In addition, because PAHs do not readily bioaccumulate within the food chain, possible human-health risks associated with consumption of fish are low. For more information on PAH exposure, see http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/phs69.html.

What are the implications of the findings? (top of page)

The study of parking-lot surfaces by the USGS and the City of Austin has implications that extend beyond Texas as parking-lot sealants are used nationwide. Findings suggest that abraded sealcoat has the potential to be an important source of PAHs in urban and suburban water bodies. In the past, sources of PAHs in urban watersheds have been thought to be dominated by leaking motor oil, tire wear, vehicular exhaust and atmospheric deposition. This study may thereby influence the discussion of strategies for controlling PAHs in urban environments.